Whilst migration may offer a viable

opportunity for some to reduce their vulnerability to environmental change,

even this ‘last resort’ mechanism is not a possibility for all. These so called

‘trapped populations’ may find their ability to migrate hampered by confounding

socio-political factors. One of the key factors in determining the capability

of an individual to adapt to such situations is thought to be capital which, broadly speaking can be

considered in six categories:

- Human Capital: the capital of persons in a household, in terms of their skills, knowledge and experience possessed

- Social Capital: the wider community networks available and also an individual’s language, accent, dialect, appearance or religion.

- Physical Capital: physical assets such as tools, machinery, cars etc.

- Natural Capital: land ownership and proximity to natural resources.

- Financial Capital: access to a bank account, capacity to borrow funds or buy insurance.

- Political Capital: access to political processes and basic human right, the extent to which they are acknowledged and provided for.

Together these determine a households’

capability to adapt, and decisions concerning the viability of migration are

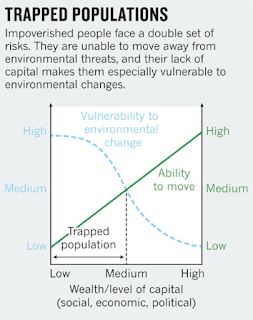

generally based upon capital availability. The UK Foresight report

(2011) addressed the issues of trapped

populations; their conceptualisation of the processes involved is depicted in

the diagram below. They considered available capital to be inversely

proportional to climatic change vulnerability, and directly related to the

ability to move. Thus, limited capital not only heightens vulnerability to a

climatic event, but also contributes to a greater level of immobility. However

not all sub-categories of capital exert an equal influence; transportation and

financial capital may have a more direct bearing on the ability to move, but

the presence of social networks beyond a crisis affected are would be

considered an indirect capital resource. The

report summarised that environmental change is equally as likely to make

migration less possible, as more probable and that that ‘trapped populations’

would be expected to become an equally as important policy concern.

The occurrence of ‘trapped

populations’ in the aftermath of recent climatic events have been discussed. Black and Collyer (2014) noted how slow onset disasters were

just as likely to result in this phenomenon as sudden events, exemplified by

unusual migration patterns witnessed during the Sahel droughts in the 1980s.

During this period, there was a big decrease in the number of young, working

age men engaging in circular migration and finding temporary employment in

other countries. This is generally something that would be expected to increase

rapidly at such a time, however the severity of the mass livestock loss in the

hyper-arid conditions destroyed the main source of capital for the majority of

people. Without stock to sell, they had no way of financing any move abroad.

Thus many found themselves with no other option but to stay put.

However, these widespread and

coincidental occurrences of immobility are not exclusive to poorly developed

countries, with Hurricane Katrina a well-documented example Here, the widely

criticised evacuation plan apparently assumed that the entire population would

have access to transportation; an assumption which strongly disadvantaged the

poorer, typically African American sectors within New Orleans. As Hartman (2006) discusses, a combination of inadequate

disaster preparedness, structural racism and inequality, generated a

catastrophe of much greater scale than it should have been. Waller (2006)

poignantly notes; ‘The

difference between those who escaped with their lives and loved ones, and those who did not, often came down

to access to a car and

enough money for gas’.

No comments:

Post a Comment